Table of Contents

Narrative

I lived in Medellín, Colombia for 3 months from late May until late August 2019. This post is written and published after the fact.

Medellín, Colombia, (pronounced me-da-jean in the local accent) like many other places I’ve been to is a complicated place with a troubled past. To the chagrin of pretty much every Colombian I’ve had the fortune of befriending, Medellín is best known to the rest of the world as the home of the late drug lord Pablo Escobar, who is also the subject of the Netflix hit series Narcos.

I watched Narcos while I was in Colombia, and the truth is that some of the stories I’ve heard from that time period are actually even more haunting than what Narcos portrays. In fact, during the 1990s, Medellín was known as the most violent city in the world, owing mainly to the fact that Pablo Escobar’s primary tactic for getting what he wanted from the government was to hold the civilian population hostage. There was a time when innocent people would literally be killed randomly in the streets and when policemen had extraordinary bounties on their heads. I came away feeling like virtually everyone who lived in Colombia during that time must have a story about someone they knew who was injured, kidnapped, or murdered.

As an outsider, even a contemporary outsider, it’s easy to look at events like these and think “Ah, that’s unfortunate” but then to subconsciously write the issues off as part of the problems of a far away land concerning people you’ll never know. However, spending time in Colombia has helped me realize that often domestic issues are inextricably tied to international causes and effects. For example, I’ve learned that, on average, Colombians are not the ones who consume the large quantity of drugs produced in their country. Rather, the vast majority of those drugs are exported to meet worldwide demand, particularly in the West from countries like the US. In many ways, drug consumption worldwide had a role to play in driving the cycles of greed and violence that long plagued Colombia.

This is, of course, only part of the complex story that is Colombia, and it’s not really the narrative I’m here to tell. Colombia has since undergone a major transformation and, while there is still a lot of crime and political instability, and there are dangerous places you absolutely should not venture to, it is not the country it was in the 1990s. And though Colombia–and Medellín specifically–still has a, sometimes well-deserved, reputation for being dangerous, I’d be remiss if I didn’t also mention that, on average, Paisan people–this is the self-given name of people from Antioquia Valley, in the heart of which Medellín can be found–are some of the nicest people I’ve met in the world, and that Colombian culture is one of the most vibrantly invigorating cultures I’ve ever experienced.

I went to Medellín because it is a famous global nomad capital (similar to Chiang Mai in Thailand in its notoriety), and after hearing so much about it, I felt I had to check it out for myself.

My first impressions of Colombia were actually all fairly negative. Before arriving at the airport in Medellín, I was warned by a few friends to ride in the front of my Uber and not to be too obvious about calling an Uber in the arrivals area of the airport. It turns out that Uber and other ridesharing services are actually illegal in Colombia, but many of them operate anyway, simply absorbing the fines incurred by drivers who get caught. When riding an Uber in Colombia, one must therefore ride in the passenger’s seat so as not to raise suspicion from the police that a normal civilian car is being used as a taxi. If you are pulled over you are meant to explain that this driver is actually a good friend of yours and that they are giving you a quick ride somewhere for no compensation at all. Thus, some of my very first moments in Medellín were spent worrying that my Uber might be pulled over by the police and that I’d end up stranded halfway between the airport and my accommodations.

(As of January 2020, Uber has actually exited the Colombian market.)

Two close friends of mine had already been living in Medellín for a couple of weeks, and had filled my head with frightening stories. For example, a friend of a friend allegedly went on a Tinder date in Medellín, and made the mistake of allowing the girl to call their car home at the end of the night. En route, two armed men jumped into the car and kidnapped him, threatening to cut off his fingers if he didn’t give them his banking information. He complied, and lost tens of thousands of dollars. Afterward, they didn’t know what to do with him, and he floated from motel to motel under armed guard for awhile until he escaped one night to tell us all his tale.

Other common stories in Medellín include accounts of people bringing women home only to be drugged, then waking up to find that she and her buddies stole everything during the night (this actually happened to someone I met in Medellín) or the use of a drug called “Devil’s Breath” to make someone susceptible to the suggestion of emptying their bank accounts.

Petty crime and theft are fairly rampant in Medellín–so much so that there’s a local phrase you can’t help but pick up: no dar papaya, which literally means “don’t give papaya.” It’s a funny phrase, but the idea is that if you cut papaya and leave it out on a platter, people are going to eat it. Your belongings are the papaya, and if you make it easy to steal your stuff, people will definitely do it. I never personally had any problems in Medellín, but this concept became real to me when, after hanging out at a local friend’s restaurant past closing, he started literally removing the lightbulbs from a string of lights he had hanging outside. Believe it or not, people will even steal the light bulbs, even in the relatively nice part of the city I lived in.

All of this is to say that when I arrived in Medellín, I was super cautious and super afraid. So much so that I considered cutting my stay short from three months to just one. My first few days, I remember employing tactics I learned in Vietnam where, even just a few blocks from where I was staying, I would never feel comfortable taking my phone out to check for directions because I didn’t want anyone to see that I was carrying something so valuable. It makes me laugh to think about that now considering that I’d eventually graduate to walking home through those same streets alone at night. (Obviously still not recommended if you’re solo traveling as a woman–checking my male privilege.)

What made me feel safer? Well, I visited a few of the definitely seedier and more crowded parts of Medellín, and I realized that my neighborhood was not particularly dangerous. I also started to realize that my two friends, having heard so many negative stories, were likely overreacting, and passing their fearful emotions along to me. There are, of course, places that you avoid in general, and places that you avoid during certain times of day, but so long as you exercise a reasonable amount of common sense, you’ll generally be fine. Most of the really bad things you hear about happening to people in Medellín happen to those who have come searching for drug or sex tourism. In three whole months in Medellín, I never personally had a single problem.

Ultimately, however, what actually tipped my decision to stay in Medellín for as long as I did was the Latin dancing scene. Let me make something clear: I’ve never been much of a dancer. Dancing is a form of expression that I’ve never felt terribly comfortable or confident in, and for me it’s always been something to tolerate, not to enjoy. But my first week, on a Friday night, I went out to Son Havana, a little salsa bar in Laureles, the upper-middle class neighborhood I was living in. Son Havana blew me away. The environment was so tangibly alive, and people were just having so much fun dancing and singing and being merry. I don’t know how to describe the experience as anything other than incredibly, incredibly invigorating. I walked out of that bar thinking to myself that 1) I’d stay in Medellín for three months and 2) I really wanted to learn more about how to participate in everything I had just witnessed.

I started taking salsa and bachata lessons, since those were the two most popular dance styles in Medellín. In the process, I found out that classes for just about anything were super affordable. I paid on the order of $15/hr for private salsa lessons with a professional teacher. I also got a membership at a nearby gym for $30/mo which included unlimited CrossFit classes, and I found a Jiu Jitsu dojo where I could take an unlimited number of classes for about $60/mo (and the price was inflated because I had to pay to rent a gi every class since I wasn’t willing to buy my own).

In fact, most things in Medellín are pretty affordable, which likely explains part of why it’s so popular amongst nomads. I’ll include a full budget breakdown later in this post, but the other stand out thing was the price of food. In Colombia, many restaurants offer a menu del día, or menu of the day. Usually the deal is a soup, a main, a dessert, and juice for between $2 and $5.

Bandeja Paisa, a local Medellín specialty, consistent of rice, fried chicharrones, ground pork, a fried egg, a potato, and a fried plantain

As a foodie, I have to say that food in Colombia often leaves a lot to be desired, however. I wasn’t impressed by Medellín’s local specialty, the bandeja paisa, which turned out to be a cut of meat, beans, rice, arepas, and sometimes fried plantains. Unfortunately, the bandeja paisa turned out to be fairly representative of most dishes in Medellín, and few things left strong impressions.

There were a few highlights, however. In search of the best menu del día in Medellín, I stumbled upon Achiote Bistro in Laureles, which became a staple in my diet (some weeks I’d literally go there 4 or 5 times). The food there isn’t exactly traditional Colombian, but it is fresh, delicious, and pretty healthy. In spending so much time at Achiote Bistro, I befriended the restaurant’s chef and co-owner, Pablo, who would become one of my closest friends in Medellín.

Pablo surprised us one day by breaking the fourth wall and asking us if we’d like to hang out. That night we all went dancing, and from there Pablo and I became fast friends. Since I love to cook, before long I was coming to Achiote every now and then to help Pablo prepare his lunch menu. One morning, Pablo brought me along on his supply run to a very local market, despite knowing that many vendors might raise their prices when they saw me. We even had a few small events where Pablo let me use his kitchen to cook something fun, the most memorable of which being when I decided to learn to make my own sancocho, a traditional Colombian soup often served at family gatherings.

Pablo would not be the only local friend I would make in Medellín, and in general I found that meeting and befriending locals was much easier in Colombia than it had been in most other places I’d been. This actually surprised me quite a bit–given Colombia’s not-so-distant violent past, and given the sheer amount of petty theft, I had a hard time understanding how and why Colombian people were so amiable, trusting, and open to strangers. On multiple occasions when I turned out not to have enough cash to pay for something, people simply trusted me to come back another time to pay the difference. Additionally, even given the sorry state of my Spanish at the time, I found that people were excited and willing to spend time with me. This is certainly different from how I felt in France, and I can’t say for certain whether the difference can be explained better by the change in environment, or by development in my own ability to make friends. It’s probably a little bit of both.

In a lot of ways I admire the Colombian people and their apparent ability to be cheerful, to enjoy life and to keep looking forward, despite recent darkness. This can be seen in the numerous dancing clubs in Medellín where locals will often dance the night away until 3 or 4 in the morning. It can also be seen in Medellín’s surprisingly well-done public transit system, which, built in the 1990s at the height of the violence, is one of the cleanest and best-maintained metro systems I’ve seen outside of Japan. I’m told that locals revere the metro as a symbol of hope and progress, thus they take care of it better than virtually any other part of the city. Medellín also has an impressive gondola system as part of their public transit network. Contrary to the “house on a hill” paradigm, in Medellín the higher up on the mountains you live, the poorer you likely are. (Most of the gang fights and other violence still happen in some of these areas.) Together with the metro system, the gondola system creates an affordable way for all Paisans to navigate the city for work and leisure.

These 300 pillars light up the open plaza at night, bringing literal light to one of Medellín’s formerly seedy areas

Likewise many of Medellín’s seedier former crime hotbeds have been transformed into symbols of light and restoration. For example, Parque de la Luz, close to the city’s government center, was once one of the more dangerous parts of the city. Today, it’s been replaced by an open plaza with 300 pillars that light up in the darkness to symbolically and literally provide light where there was once darkness. (I should note, though, that this is still not an area generally recommended to foreigners to visit at night on their own.)

Are things perfect? Of course not, and people are not ignorant of the facts. It’s not super common, but on occasion after making conversation with Uber drivers I’d realize that not only had they spent time in the US, they’d actually illegally lived and worked there and, in some cases, had actually been deported, which is why they were now back in Colombia driving for Uber. One girl I went on a couple of dates with also expressed an almost single-minded desire to emigrate to the US. (Which, of course, being a US citizen myself, makes the dating dynamic a bit awkward.) I don’t bring these examples up to hold the US up as a shining beacon of hope and progress–in many ways it is, in many more ways, it is not–but rather to illustrate that a desire to escape does sometimes exist in Colombia.

Colombia and Medellín still have plenty of problems, ranging from fractured and militant political groups to the still booming drug trade. Yet this is a city, a country, and a people that has lost much, but, at least from my outside perspective, refuses to lose more by letting that define them.

The spirit of the Colombian people, the ease with which I could make friends, the low cost of living, and availability of cheap outlets for new hobbies all culminated in a very positive experience for me in Colombia. Probably my only complaints were the food, and Medellín’s rather small town feel. (I actually generally prefer bigger cities with more going on.) While I don’t know when or if I will return, I could see myself spending more time in Colombia some day.

Living and Working

There are two major areas that stand out to expats in Medellín: El Poblado and Laureles. El Poblado is the main tourist center of the city, and is where you’ll encounter a lot of foreigners. It’s also the center of nightlife in Medellín–bars, clubs, dancing, restaurants. At night, the party in El Poblado seems to stretch far into the morning, and the streets will be lined with prostitutes. While El Poblado is generally pretty safe, it is somewhere you can find trouble if you go looking for it. It’s certainly the louder and livelier of the two options.

Laureles, which is where I stayed, is much more down-to-earth. While you will encounter foreigners in some of the more popular cafes, it has a more local and less gentrified feel to it. It is, however, an upper-middle class neighborhood, and therefore nicer than many other parts of the city by Colombian standards. Laureles was, in fact, so clean and so nice that in my first week when I arrived I had serious cognitive dissonance–it absolutely did not match the picture of Colombia that I had in my mind. While Laureles is smaller and quieter, there are still a lot of good restaurants and cafes in the area. For those who want to party (or go out and salsa dance!!) there is a strip nearby called Setenta, which houses a lot of the nearby bars and clubs.

I ended up in Laureles based on the recommendation of a friend of a friend, and don’t regret the choice, though I’m sure staying in El Poblado would have been a very different experience.

I lived in a new coworking/coliving space called Conomad House. I can’t say that it was anything particularly special, but it was cheap and 3 of my friends were staying there with me. The $350/mo I paid there included a small working space with blazing fast internet, but the walls were thin and the neighbors were loud, so I’d often be woken up earlier than I wanted to be. The location was good, situated in the heart of Laureles, and I spent most of my days working from home.

If I end up back in Medellín some day, I think I’d likely try to get myself a room in a penthouse, preferably in Laureles. My impression is that these can be quite affordable once split amongst multiple people–something like $1800/mo for 3 bedrooms.

Recommendations

Here are my favorite spots in Medellín. Keep in mind I spent most of my time in Laureles:

- Food

- Achiote Bistro

- Fresh, delicious, healthy food in a cool environment

- Tell Pablo, the chef, that Daniel says hi!!

- Arepitas Rellenitas

- Ordinarily, I honestly despise arepas. This is the only place I’ll go to eat them!

- Restaurante La Aldea

Sancocho from Restaurante La Aldea in Santa Elena. One of the best soup dishes I’ve probably had in my life.

- This one’s out of the way in Santa Elena, but well worth the trek

- Best sancocho in the world!! Delicious, savory, smoky. My chef friend Pablo took me here and I was not disappointed.

- So good that I went all the way back one more time before I left Colombia

- Caduff Pasta Fresca

- Go for their lunch menú del día–handmade pasta at an incredibly low price point

- Empanadas La Catedral

- Delicious empanadas!!

- Los Perritos

- Colombian-style hotdogs inundated with tons of other unhealthy stuff that makes it delicious but terrifying to eat

- Really only need to go here once haha

- Restaurante Mistura

- First tried this restaurant in Cartagena, but they do a very interesting fusion of Latin and Asian cuisines

- A little on the pricier side for Colombia

- Chef Burger

- Seldom would I recommend a burger place outside of the US, but Chef Burger’s patties made from high quality ground beef mixed with Argentinian chorizo are simply delectable

- SMASH Avocaderia y Cafe

- A more casual and healthy meal, but a common staple in my diet in Colombia

- Casal Bakery

- A staple for me because I lived right above it

- Very good value for menú del día and delicious desserts!

- Food otherwise is just OK, but they often serve traditional Colombian dishes

- Olivia Pizzeria Laureles

- Good place for a pizza if you’re craving one!

- Achiote Bistro

- Bars and Breweries

- 3 Cordilleras

- Cool craft brewery that has an awesome deal on craft beer flights (something like $20 for 5 or 6 very generous glasses of beer)

- Often have live music events and concerts at the brewery!

- BBC Cervecería

- Awesome craft beer! Their stout is quite good

- Used to come here to hangout a lot

- 3 Cordilleras

- Salsa Clubs

- Son Havana

- The place that originally made me fall in love with salsa

- Live music here past ~11 or 12 on Friday nights!

- El Tibiri

- A pretty local spot that’s usually pretty packed

- It’s sort of in a poorly ventilated basement, so be warned that it gets HOT!

- Dance Free

- A popular salsa school/club in El Poblado

- I only went once, but was impressed–lots more space to dance here than most other places I’ve been

- Son Havana

- Dance Schools

- Euforia Escuela de Baile

- My salsa teacher, Catalina, was super awesome!

- Very affordable private lessons ~$15/hr

- Solo Ritmos

- Great group classes at a very affordable price

- Most of the instructors here don’t speak English, however

- Euforia Escuela de Baile

- Gyms and Fitness

- 360 Fitness

- Not the nicest gym you’ll ever go to in the world, but very affordable at $25/mo

- For $35/mo you also get access to unlimited CrossFit

- Checkmat Colombia-Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu

- Cool dojo to train Jiu-Jitsu

- Unlimited classes for ~$60/mo

- Instructor speaks some English, though will mostly instruct in Spanish

- 360 Fitness

- Sightseeing / Activities

-

Coffee Plantation Tour

- Colombia is famous for its coffee! And there are many plantations accessible from Medellín.

- Learn about the coffee process, and pick your own coffee cherries.

- Medellín Bike Tour

- Website is a little janky, but the tour is high quality

- Be advised that the tour is catered toward people who enjoy cycling (and have a relatively decent fitness level). Not for the faint of heart.

- Free Walking Tour

- Covers a lot of places you probably don’t want to go without a group

- Ride the Gondolas to Parque Arví

- Plaza Botero

- Featuring many statues from celebrated Colombian artist Fernando Botero

- The Free Walking Tour above will take you here briefly

-

- Side Trips

-

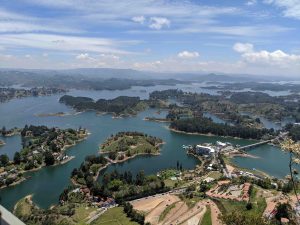

Guatapé

- The site of the La Piedra, a very, very large rock with an incredible view, and a very colorful city that actually feels more Mexican than Colombian at the end of the day

- A couple of hours from Medellín by bus

-

- Miscellaneous

- Lava en Happy Laundry

- I came here all the time to have my laundry done for cheap

- Staff is super friendly, and most of them speak very good English

- If you drop off in the morning, can have your laundry done same day

- Lava en Happy Laundry

Flower Festival

Believe it or not, Colombia is one of the world’s largest exporters of flowers, and Medellín is one of the flower capitals of the country. Thus, every year in August Medellín hosts a huge Flower Festival, which involves parades, pop-up events, decorations, the whole nine yards. I hadn’t planned on it, but I had the good fortune to be living in Medellín during this event in 2019.

On the whole, I think it was a cool experience–silleterras, the traditional flower displays–are really quite extravagant, and cool to see. The legend goes that once upon a time before the mountains opened Antioquia Valley to more convenient forms of travel, people would literally put chairs on their back and carry people–often the wealthier class–up and down the mountains on those chairs. These days, one can still see the chair-like nature of the silleterras that people carry on their backs, but nowadays the carry flowers, not people.

I personally went to up into the mountains to see some of the flower farms and watch the process of making the silleterras. I was a little disappointed to learn that some of the more stylized designs involving text or brands were actually spray painted, but nonetheless still very impressed by the level of craftsmanship that goes into these works of art.

I also had the chance to go to a few of the concerts that happened during the week of the festival, and I tried to make it out to watch the grand parade featuring Colombian cultural dances and flower displays, etc. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to get a very good spot for the parade, so that experience was fairly lackluster.

At the end of the day, however, I’m not sure if I would recommend that someone make a special trip to Medellín just for this festival. At the very least, if you do, go the extra mile and reserve yourself an actual seat somewhere for the big parades–watching the parades from a distance through a hole in the very large crowd isn’t terribly gratifying.

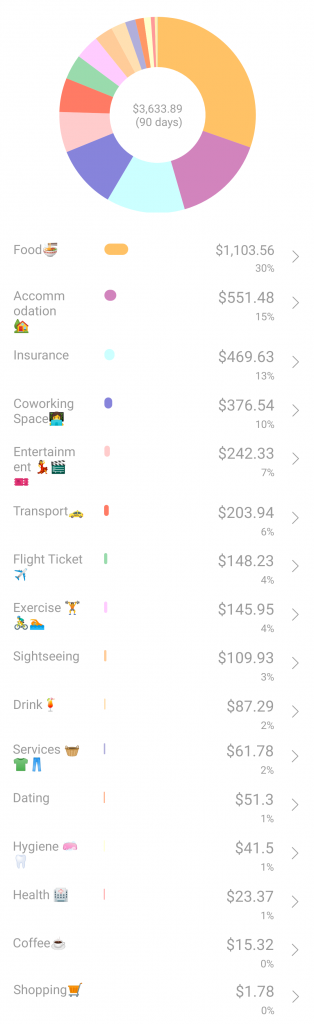

Budget Breakdown

My typical monthly living budget while abroad is around $2000/mo, and in Medellín I actually found myself struggling to spend anywhere near that amount of money.

Here’s a breakdown of my budget from May 30 to August 27 (exactly 90 days):

I could have spent much less on food, if I had tried, but I didn’t. I split my $350/mo housing cost in half, and logged half of it as coworking, since the arrangement included coworking. I tended to get free coffee out of that deal, too, so spent very little on coffeeshops. The majority of my services expenses were laundry, costing me ~$6 every 10-15 days. I ultimately didn’t need the insurance I purchased, so I probably could have dropped that. These numbers also include a side trip I took to Cartagena for a few days, which probably cost me ~$200 in total.

My only health expense in Medellín was a routine dental cleaning. In retrospect, I honestly wouldn’t recommend Medellín for dental care–the cleaning was cheap, but the technology wasn’t very modern, and I didn’t feel the dentist was terribly thorough (yes–the dentist himself did the cleaning!). Dental care was much better in Chiang Mai, Thailand, and in Mexico City, Mexico (which I’ll publishing my thoughts about soon!).

But as you can see, despite trying to spend more I ended up spending only about $1250/mo in Medellín. My life was pretty comfortable for that amount–I ate out for pretty much every meal, sent my laundry out for service, and used Uber as my main mode of transport. The only other thing I might have considered splurging more on is a housing upgrade as I mentioned earlier.